On January 14–15, 2026, the Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission’s in-house science and knowledge service, presented the results from its preparatory study on textile products – the 3rd Milestone Technical Report on Textiles.

What the 3rd milestone covers

The report focuses on two analytical pillars:

- Base case analysis: The JRC divides the apparel market into three product categories – Knitted, Denim, and Other Woven – establishing environmental and economic benchmarks against which future improvements are measured.

- Design options analysis: The study evaluates specific technical interventions, including repairability approaches, recyclability scores, and recycled content targets. The JRC assesses these options for feasibility, cost, and potential environmental benefit relative to the base case.

Together, these analyses form the technical foundation for the EU’s Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR).

The JRC’s 3rd Milestone serves as the evidence base that will, through the 4th and final milestone and the textiles-specific delegated act, translate selected design options into mandatory Digital Product Passport (DPP) requirements for apparel.

While the report remains open for stakeholder feedback until the end of March, its direction is clear. The EU is moving from sustainability ambition to concrete, testable, and enforceable requirements under the ESPR and the forthcoming Digital Product Passport for apparel.

The European Commission deserves credit for a transparent process. At the same time, discussions during the workshop and Q&A suggest that many of these proposals will not pass into final legislation without significant debate.

Key takeaways

- The 3rd Milestone confirms that DPP requirements for apparel are moving from theory to implementation.

- Repairability was eliminated as a design option due to concerns that it would heavily burden the industry without actually fixing the real problem.

- Robustness testing establishes a market floor but says little about durability.

- Recyclability and recycled content rules risk misaligned incentives, particularly around PET bottles.

- Average-based footprint scoring could disadvantage SMEs who cannot afford expensive calculations and data verification.

Early friction points

Stakeholders raised immediate concerns about the report’s high-level categorisation of the industry. Many warned that broad categories risk averaging out the impact of worst-performing products. The workwear and PPE sectors also flagged the danger of being subjected to consumer-grade testing standards rather than existing industrial norms.

Beyond categorisation, strong reactions centred on the balance between information requirements and performance requirements. From the JRC’s perspective, information requirements are often a necessary first step: without reliable, standardised data, setting meaningful performance thresholds is difficult, particularly in areas where test methods are immature or data availability is uneven across the market.

This staged approach is defensible. However, several stakeholders questioned whether an initial reliance on disclosure alone will be sufficient to curb unsustainable business models. The concern is not whether information requirements are needed, but whether they will be followed quickly enough by enforceable minimum standards.

Rather than revisiting this broader debate, the following sections focus on the design options that generated the most friction during the workshop.

Repairability: A retreat from ambition?

Repairability is defined as the capacity of a product to be repaired – not the likelihood that it will be repaired.

Despite ESPR explicitly highlighting durability and repairability as priority areas, the JRC concludes that objectively measuring repairability for apparel is nearly impossible. As a result, instead of a mandatory repairability score, the report proposes a voluntary information requirement allowing brands to list contact details for their own repair services.

This represents a significant retreat from the repairability ambitions outlined in the ESPR and described in the PEFCR for Apparel and Footwear.

More controversially, the report argues that strict repairability rules would often conflict with the “creative nature of the fashion industry.” Regulation, however, exists to change industry behaviour. Accepting creativity and trend cycles as reasons not to regulate repairability risks protecting the very business models that created today’s waste problem.

Reuse and repair remain the most effective ways to extend a product’s life during the use phase. While there’s a clear focus on dealing with waste through recyclability and recycled content requirements, it is remarkable how passive the report seems to be in preventing the waste. Without stronger incentives or requirements, repairability risks remaining a theoretical concept rather than a practical lever for waste prevention.

From durability to robustness

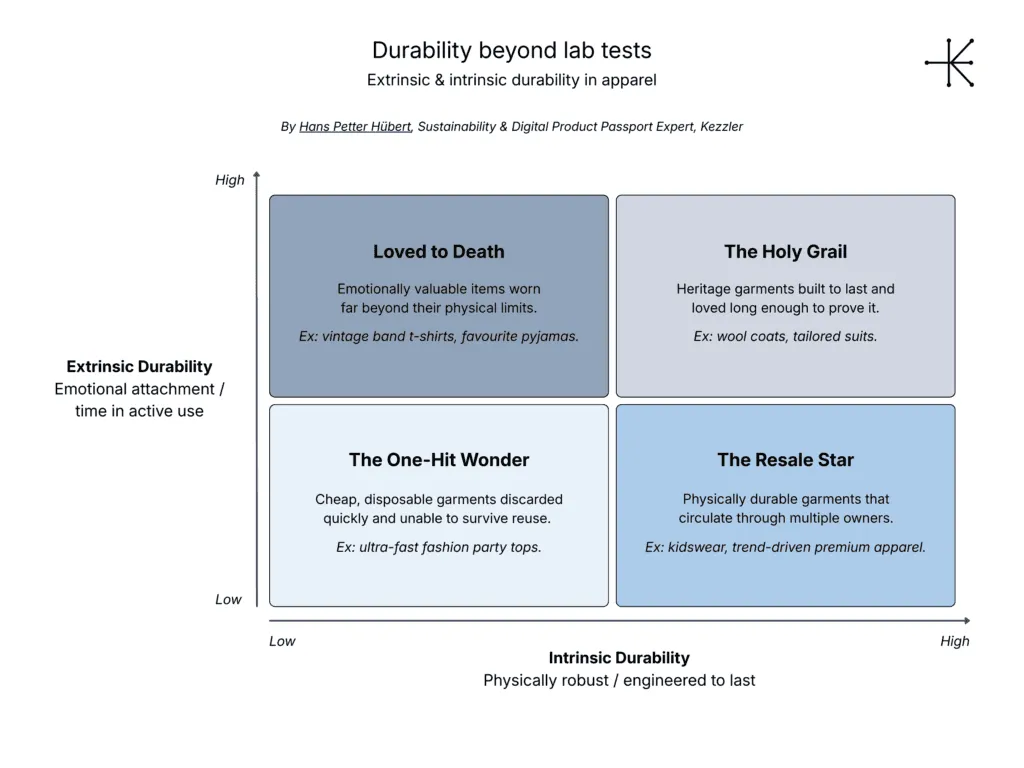

Durability in apparel is inherently complex. Two distinct dimensions are at play:

- Intrinsic durability: the physical, engineered ability of a garment to withstand wear, washing, and time.

- Extrinsic durability: how long a garment is actually kept and used, driven by emotional attachment, fit, and evolving trends.

Because policymakers cannot regulate human boredom or fashion cycles, the scoring system focuses on intrinsic durability. Durability, however, implies time. Without time-based testing, intrinsic durability effectively becomes robustness.

Robustness testing successfully removes the worst-performing products from the market. However, by emphasising cosmetic ageing (such as pilling and colour fading) and de-emphasising structural integrity, the system risks confusing “staying pristine” with “staying intact.”

This creates a scenario where a cheap polyester garment may score higher than a heritage denim product designed to last decades but expected to fade over time.

Robustness therefore functions as a necessary floor – but not as a complete durability signal in a circular economy.

Durability beyond lab tests: extrinsic & intrinsic

Durability cannot be meaningfully assessed without considering how long products actually circulate.

Item-level Digital Product Passports make it possible to capture real-life lifecycle events such as repairs, resale, and ownership duration. This enables a more nuanced understanding of durability that combines intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

This distinction can be illustrated through a simple durability matrix:

Current robustness testing captures only one axis of this matrix. Item-level DPPs have the potential to make the missing dimension visible.

Over time, this real-world data could support more evidence-based durability metrics and, at least theoretically, pave the way for fairer eco-modulation fees.

Recyclability score and recycled content: The PET bottle dilemma

Textile waste remains one of the most unresolved failures of the linear economy. Global estimates suggest that more than 100 million tonnes of textile waste are generated annually, with the vast majority landfilled or incinerated.

Scaling textile recycling requires both sufficient waste inflow and predictable demand for recycled fibres. While separate textile collection became mandatory in the EU in January 2025, it will take years before collection, sorting, and recycling operate at scale.

To support future recycling, the JRC proposes a recyclability score as a design option. Mono-material products score higher, while products containing more than 15% elastane are classified as non-recyclable under the proposed methodology.

Recycled content requirements are introduced as a performance requirement in parallel. Originally envisioned as fibre-to-fibre recycling of post-consumer waste, the definition now also includes open-loop sources, most notably PET bottles, as well as industrial and pre-consumer waste.

This pragmatic decision introduces two structural risks:

- Broken incentives: Cheap PET undermines investment in textile-to-textile recycling.

- System inefficiency: Waste is diverted from highly functional bottle recycling systems into textiles, where end-of-life outcomes remain uncertain.

As Louisa Hoyes, Segment Director Textiles at TOMRA, puts it:

“From a sorting and recycling infrastructure perspective, both recyclability requirements and recycled content targets are essential, but they must be aligned. If products are designed for recyclability but there is no demand pull through recycled content mandates, investment stalls. Equally, if recycled content targets rely too heavily on bottle-to-fibre inputs, the textile-to-textile recycling ecosystem may struggle to scale. The system only works when design, sorting capability, and end-market demand develop in parallel.“

Circular value chains require not only ambition, but predictable framework conditions. Uncertainty makes long-term investment harder.

Environmental footprint: The “average” loophole

To assess environmental impact, the JRC proposes one out of two simplified footprint metrics focused on the manufacturing phase only:

- Carbon footprint (CF): approximately 6% of total lifecycle impact

- Environmental footprint (EF): approximately 20% of total lifecycle impact

While this approach aims to reduce administrative burden, it also reflects a deliberate choice to prioritise areas where harmonised methodologies already exist.

To further ease compliance, brands may rely on secondary data or default to average scores. This creates two challenges:

- SME disadvantage: Demonstrating better-than-average performance requires costly primary data collection and verification.

- The average loophole: Brands can revert to average data if primary calculations are unfavourable.

Combined with weight-based calculations and the exclusion of the use phase, heavier, longer-lasting garments risk appearing worse than lightweight products with shorter lifespans.

Strategic compliance: Preparing for the 4th milestone and beyond

The JRC’s 3rd Milestone confirms that Digital Product Passports for apparel are becoming real. It also highlights the difficulty of balancing sustainability, competitiveness, and fairness – particularly in an industry dominated by SMEs.

Launching a lighter initial version of the DPP, learning from real-world implementation, and refining requirements over time is a pragmatic approach. Many brands are already aiming beyond minimum compliance, recognising that item-level digital identifiers unlock new operational insight and new business models.

The DPP will not transform the industry through mandatory disclosures alone. Its real impact lies in what becomes possible when products are digitally connected throughout their lifecycle.